Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence

Joe J. Tjandra, M.D., Sharon L. Dykes, M.D., Ravin R. Kumar, M.D., C. Neal Ellis, M.D., Sharon G. Gregorcyk, M.D., Neil H. Hyman, M.D., W. Donald Buie, M.D., and the Standards Practice Task Force of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

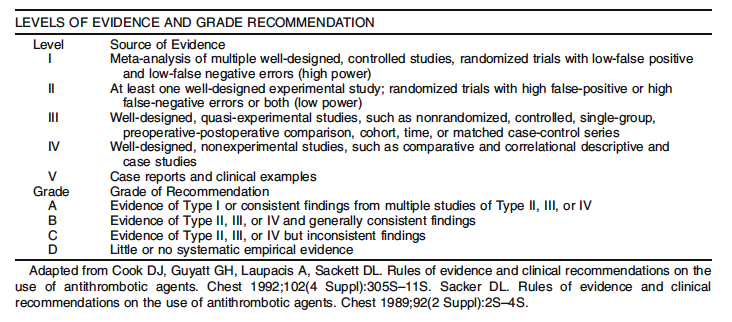

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring highquality patient care by advancing the science, prevention, and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. The Standards Committee is composed of Society members who are chosen because they have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and rectal surgery. This Committee was created to lead international efforts in defining quality care for conditions related to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive, and not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on which decisions can be made, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. These guidelines are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers, and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed by the topics covered in these guidelines.

It should be recognized that these guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all of the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

METHODOLOGY

A MEDLINE search was performed, from 1966 to February 2006, using the key words “fecal incontinence,” “anus,” “implants,” “bowel sphincter,” “graciloplasty,” and “artificial sphincter.” Selected embedded references also were reviewed. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was queried.

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Fecal incontinence is defined in a consensus conference report in 2001 as Brecurrent uncontrolled passage of fecal material for at least one month, in an individual with a developmental age of at least 4 years. 1 Incontinence to flatus also may cause substantial impairment of quality of life and should be considered in the definition. Because of the lack of standardization, the true prevalence of fecal incontinence is difficult to determine.2 Quoted prevalence rates vary widely from 1.4 to 18 percent, with higher rates in nursing home residents, parous females, patients with cognitive impairment or neurologic disorders, and the elderly.3–5 In the geriatric and institutionalized population, the reported rates of fecal incontinence are approximately 50 percent.5,6 Female patients predominate in most series, although epidemiologic studies do not demonstrate any gender differences.2,7 It is postulated that this is the result of the age and gender of patients who seek treatment.

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Continence is dependent on the complex relationships between the anal sphincters, pelvic floor function, stool consistency, rectal compliance, and neurologic function. Disease processes or structural defects that alter any of these aspects can contribute to fecal incontinence. In many cases, the etiology of fecal incontinence is multi-factorial and it is not possible to ascertain the relative contribution of each factor. A full discussion of contributing factors is beyond the scope of a practice parameter.

Obstetric injury is the most commonly cited cause of incontinence in females.2 Sphincter disruption is clinically recognized in approximately 10 percent of all vaginal deliveries, but many other females have occult sphincter damage. Although the incidence of sonographic damage to the sphincters after childbirth varies among studies, it occurs in approximately 30 percent of first vaginal deliveries.8,9 One third of these are associated with new symptoms of incontinence or urgency. Independent risk factors include forceps delivery, occipitoposterior position, and prolonged second stage of labor. The extent of a sphincter defect does not necessarily correlate with the degree of fecal incontinence, highlighting the complexity of obstetricrelated disturbances.

ASSESSMENT

1. Evaluation of fecal incontinence should include consideration of severity and impact. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Severity instruments assess type, frequency, and amount of incontinence. Impact questionnaires address quality of life and attempt to evaluate the effect of incontinence on emotional, occupational, physical, and social function. Both should evaluate these relatively subjective factors with reliability and validity.10

Severity measures can be divided into two types: grading scales and summary scales. Despite the existence of numerous severity scales, there are limited data with regard to their validity and reliability. Grading scales assign numeric scores to degrees of fecal incontinence and/or types of incontinence (flatus to solid stool) but lack assessment of frequency and can be imprecise.11–18 Summary scales have greater validity19–32 and can be used to demonstrate improvement in continence scores after treatment or decline in scores as a consequence of a medical/surgical intervention.20,22,23,29–31 Summary scales also have been shown to correlate with quality of life instruments by evaluating lifestyle scores.19,20,33,34

A validated quality of life instrument for fecal incontinence does exist.35 Furthermore, fecal incontinence is a component of other disease specific quality of life tools.36–38

DIAGNOSIS

1. A problem specific history and physical examination should be performed. Level of Evidence: Class V; Grade of Recommendation: D.

A detailed medical history may help to elicit contributing or exacerbating factors, such as gastrointestinal or neurologic disorders. An obstetric account or history of previous anorectal surgery or perineal trauma can direct/prompt a more focused examination.

Inspection of the perianal skin may reveal excoriation, surgical scars, or fistulas, and the anus may be noted to gape upon spreading the buttocks. Mucosal or full thickness prolapse may be elicited with a Valsalva maneuver. Digital examination may provide a rough estimate of resting and squeeze pressures and is helpful to evaluate for a rectal mass or the presence of impacted stool, which would suggest overflow as a possible mechanism for incontinence. Anoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy may help to identify hemorrhoids, inflammatory bowel disease, or neoplasms.

2. Endoanal ultrasound is usually the procedure of choice to diagnose sphincter defects in patients with suspected sphincter injury. Anorectal physiology studies may be helpful in guiding management. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

When performed by an experienced clinician, endoanal ultrasound approaches 100 percent sensitivity and specificity in identifying internal and external sphincter defects.39–41 However, as noted previously, the presence of a sphincter defect does not necessarily correlate with incontinence. Of 335 patients with incontinence, 115 patients who were continent, and 18 asymptomatic female volunteers, ultrasonography detected sphincter defects in 65, 43, and 22 percent, respectively.42

Anal manometry is a simple, noninvasive method of measuring internal and external anal sphincter tone, and the length of the high pressure zone of the anal canal. There are few large scale studies that have attempted to validate the role of anorectal physiologic testing in predicting response to treatment options for fecal incontinence. There are significant manometric variations even within

“normal” asymptomatic subjects, dependent on age, gender, and parity. Although the findings of anorectal physiology studies do not consistently correlate with severity of fecal incontinence, they may influence the management decisions that are ultimately selected for treatment.43–45

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

1. A trial of increased fiber intake is recommended in milder forms of fecal incontinence to improve symptoms. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B

Nonoperative therapy is usually the first maneuver to improve the symptoms of fecal incontinence. Most patients with mild fecal incontinence should usually receive an initial trial of nonoperative management.Fecal incontinence is commonly exacerbated by liquid stools or diarrhea.46,47 Stool bulking agents include high fiber diet, psyllium products, or methyl cellulose. An increase in dietary fiber may improve stool consistency by absorbing intraluminal water. Supplementation of diet with psyllium is associated with improved stool consistency and a decrease in symptoms.48 The recommended dose of dietary fiber is 25 to 30 grams per day. Gradual increase of fiber intake during a period of several days can reduce symptoms, such as abdominal bloating and discomfort, that may be associated with increased fiber intake. Fiber supplements in the form of powder, granule, or pill often facilitate this goal. Dairy products are problematic in patients with lactose intolerance.49

2. Anti-diarrheal agents, such as adsorbents or opium derivatives, may reduce fecal incontinence symptoms. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: C.

Adsorbents, such as kaopectate (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Peapack, NJ), act by absorbing excess fluid in the stool. Commonly used opium derivatives are loperamide (Imodium, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, Fort Washington, PA), diphenoxylate hydrochloride plus atropine sulphate (Lomotil, Searle, Chicago, IL), codeine, and tincture of opium. The effects of opioids include decreased intestinal motility, decreased intestinal secretion, and increased absorption. Loperamide can slow bowel motility and increase fluid absorption. In addition, loperamide increases resting anal sphincter pressure.50 The usual dosage of loperamide is 2 to 4 mg followed by titration up to a total of 24 mg per 24 hours in divided doses.

Diphenoxylate can produce central nervous system (CNS) side effects and has greater potential for abuse.51,52 The usual dosage of diphenoxylate is one tablet every three to four hours. Loperamide and codeine may be superior to diphenoxylate in the treatment of symptomatic diarrhea.51 Tincture of opium is less commonly used because of the potential for CNS side effects and addiction.

3. Enemas, laxatives, and suppositories may help to promote more complete bowel emptying in appropriate patients and minimize further post-defecation leakage. Level of Evidence: V; Grade of Recommendation: D.

Bowel management programs often are used to relieve severe constipation in spinal cordinjured patients.53–55 Patients with severe constipation often experience overflow incontinence as a result of constant seepage of stool from the full rectum.56 An enema program in such patients may help to minimize episodes of incontinence. Evaluation and management of abnormal colonic transit also can be helpful.57 Otherwise, there is little evidence to guide clinicians in the use of these therapies for fecal incontinence in patients with an intact spinal cord.

4. Biofeedback is recommended as an initial treatment for motivated patients with incontinence with some voluntary sphincter contraction. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Biofeedback may be considered a firstline option for many patients with fecal incontinence who have not responded to simple dietary modification or medication.58 The benefit of biofeedback is variable and improvement in as many as 64 to 89 percent of patients has been reported.30,58 Biofeedback is performed to improve sensation, coordination, and strength. Supportive counseling and practical advice regarding diet and skin care can improve the success of biofeedback. Biofeedback may be considered before attempting sphincter repair or for those who have persistent or recurrent symptoms after sphincter repair. It may have a role in the early postpartum period in females with symptomatic sphincter weakness.59 Biofeedback and a pelvic floor exercise program can produce improvement that lasts more than two years.60–62 More than 75 percent of the initial responders to biofeedback had a sustained symptomatic improvement and 83 percent reported an improved quality of life.63

Biofeedback home training is an alternative to ambulatory training programs, especially in the elderly.64 Improved rectal sensation after biofeedback is one of the most consistent predictors of improved continence.65 However, Bstandard care^ (advice and education) alone has been shown in a randomized trial to be as effective as biofeedback therapy.66

5. An anal plug is effective in controlling fecal incontinence in a small minority of patients who can tolerate its use. Level of Evidence: V; Grade of Recommendation: D

The anal plug enables controlled fecal evacuation and helps reduce skin complications.67 However, most patients do not tolerate the anal plug because of discomfort.68 No correlation was found between the results of anorectal physiology studies and the benefit or inconvenience of using the plug.69 A trial of the anal plug in patients quickly reveals whether the patient will find it an effective and acceptable option.70

SURGICAL OPTIONS

1. Sphincter repair is appropriately offered to highly symptomatic patients with a defined defect of the external anal sphincter. Level of Evidence: II; Grade of Recommendation: A.

Anal sphincter repair often confers substantial benefits in patients with localized external sphincter defects. Short term outcomes suggest good to excellent resultsin31to83percentofpatients.71–78 Most of the outcome data on anal sphincter repair pertain to patients with an anterior sphincter defect from obstetric trauma rather than repair of sphincter disruptions from surgical trauma, such as a fistulotomy or sphincterotomy.

However, the benefits of sphincteroplasty tend to deteriorate with long-term followup. In a study from St. Mark_s Hospital, the initial success rate of 76 percent after an overlapping sphincter repair deteriorated dramatically with time.71,79 After five years, no patient was fully continent to flatus and less than 10 percent were fully continent to solid and liquid stool. Similar results have been reported by others. After five to ten years, only 40 to 45 percent of patients were satisfied with the functional outcome.80,81 Similarly, after a median of 69 months, only 14 percent of patients at the Cleveland Clinic were completely continent.82 Adjuvant biofeedback therapy after surgery may improve quality of life and help sustain symptomatic improvement with time.83

No single preoperative manometric variable can predict outcome after a sphincter repair.84 There also is controversy about whether pudendal nerve conduction studies can be used to predict outcome after a sphincter repair.85–89

2. Overlapping or direct sphincter repair yield similar results, as long as adequate mobilization of both ends of the sphincters are performed. Level of Evidence: II; Grade of Recommendation: A.

Overlapping sphincteroplasty, as described by Parks and McPartlin in 197190 and later modified by Slade et al.,91 has been the predominant technique of repair used by colon and rectal surgeons during the last three decades. However, a randomized trial showed no benefit of an overlapping repair compared with a direct repair, as long as both ends of the external sphincter were adequately mobilized and the anorectal ring was plicated.43 In another non-randomized study, the outcome after a sphincter repair was similar among different operative techniques (end to end, overlapping repair, and plication). Severe denervation and pudendal nerve damage often are found in patients who remain incontinent after a sphincter repair.92,93 Dyspareunia might follow sphincteroplasty, although the true incidence has not been well documented.

3. Repeat anal sphincter repair could be considered in patients who have recurrent symptoms and residual anterior sphincter defect after a previous sphincter repair. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Failure after sphincter repair might be related to persistence or recurrence of the external anal sphincter defect as shown by endoanal ultrasound.94,95 Previous sphincter repair does not seem to affect the clinical outcome of a subsequent repair. In a comparative study,96 the outcome was similar between patients with or without a previous sphincter repair; good results were obtained in 50 and 58 percent of patients, respectively. Nevertheless, the long-term benefit of a repeat sphincter repair was only modest—similar to an initial repair.97

4. Repair of the internal anal sphincter alone has a poor functional outcome and is not generally recommended. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

The role of internal anal sphincter (IAS) repair alone in restoring the resting anal canal pressure is not well defined and this procedure is typically ineffective.98–100 Island anoplasty into an area of IAS defect improved fecal continence in 13 of 14 patients in one report,100 but there was a high incidence of wound breakdown.

5. When passive fecal incontinence caused by internal sphincter dysfunction is the predominant symptom, injectable therapy seems to be effective and safe, although its long-term efficacy has yet to be defined. Level of Evidence: II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Effective treatment for IAS dysfunction is lacking. Recently, there have been attempts to augment the bulk of the IAS by injection therapy into a defect in the IAS or around an intact, but degenerate, IAS. Of the agents described, injectable silicone biomaterial has been the most studied.45,101,102 The bulking effect of the injected silicone particles with subsequent collagen deposition around the IAS helps to enhance fecal continence. The greatest improvement in fecal continence occurs between one and six months after injection therapy.45 The site of injection could be in the intersphincteric plane or into the submucosa. The latter approach is more likely to be associated with infection, erosions of implants, or anal pain caused by the superficial location of the injected material.103 More precise injection into the intersphincteric space with ultrasound guidance may improve the outcome.45

Other injectable agents currently being evaluated include carboncoated beads. In a preliminary study, injection into the site of the sphincter defect was associated with improvement in the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Scale Scores from 11.89 at baseline to 8.07 after a mean followup of 28.5 months.104 Longterm safety and efficacy data are lacking.

6. Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is a promising modality for fecal incontinence. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Sacral nerve stimulation has been associated with encouraging early results with low morbidity. It seems to be better than optimal medical therapy with bulking agents, pelvic floor physiotherapy, and dietary management.44SNS comprises a diagnostic peripheral nerve evaluation (PNE) stage followed by a permanent therapeutic implantation stage. Patients receive a permanent sacral nerve implant if the diagnostic stage produces clinical improvement, marked by a reduction in frequency of episodes or days of fecal incontinence by at least 50 percent based on a twoweek diary.44

Although up to 20 percent of patients do not show adequate response to PNE, this screening test seems to have a 100 percent positive predictive value, because all patients who respond to temporary test stimulation (PNE) seem to benefit from a fullstage SNS.44,105 Eightythree to 100 percent of those achieving permanent implantation maintain an improvement of greater than 50 percent at a mean followup of 10.5 to 24 months.105–110 Although an improvement in continence occurs in most patients, continence to solid and liquid stool sinpatients with a permanent implant ranges from 44 to 73 percent.44,106–110 SNS also has the potential to benefit patients with both fecal and urinary incontinence.111 Patients with limited structural sphincter defects of the internal or external sphincter have been treated with SNS with reported benefit.44,107,109,111 The improvement with SNS in diverse groups of patients reflects the limitations of current knowledge about pelvic floor physiology as well as the precise mechanism of action of SNS.

The incidence of complications with SNS ranges from 5 to 26 percent in various studies. 44,107–110,112 The screening test (PNE) has a very low complication rate.44,109 Complications requiring permanent explanation of the SNS device seem to be uncommon.44,107–110,112 The most common complication in clinical series was pain at the site of the neurostimulator generator, especially in thinner patients.105 Infection of the wound or the sacral nerve implant is rare (<5 percent), if appropriate techniques are used.105,107 Currently, SNS is not FDAapproved for fecal incontinence in the United States, although it is approved for urinary incontinence.

7. Post-anal repair or total pelvic floor repair has a limited role in the treatment of neuropathic fecal incontinence. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

The principle of post-anal repair is to reduce the obtuse anorectal angle113 and has been advocated for patients with weak sphincters but no anatomic sphincter defect114; however, others have failed to show any correlation between the anorectal angle and the outcome of surgery.115 In a study of post-anal repair in a well defined group of patients with neuropathic fecal incontinence, the St. Marks group concluded that the longterm results of post-anal repair successfully relieved fecal incontinence in only 33 percent of patients at five to eight years post operatively.116 Total pelvic floor repair fared slightly better for neuropathic fecal incontinence with 55 percent of patients continent to solid and liquid stools 15 months after the procedure.117

8. Dynamic graciloplasty may have a role in the treatment of severe fecal incontinence when there is irreparable sphincter disruption. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Dynamic graciloplasty consists of a transposed gracilis muscle used to encircle the anal canal, which is stimulated electrically with an implantable pulse generator.118 Dynamic graciloplasty is most appropriate for patients with extensive sphincter disruption precluding a surgical repair, severe neural damage, or congenital disorders, such as anal atresia.119,120

The results of dynamic graciloplasty have been variable. Although moderately good results are reported from a small number of high volume centers, multi-center trials that included less experienced surgeons have shown a high morbidity and poorer functional outcome. Dynamic graciloplasty restores continence in approximately 35 to 85 percent of patients.119,120 Currently, dynamic graciloplasty is not FDA approved in the United States.

9. The artificial bowel sphincter has a role in the treatment of severe fecal incontinence, especially in patients with significant sphincter disruption. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

The artificial bowel sphincter provides good restoration of continence for solid and liquid stool in patients who retain the device. In a small study, more than 50 percent had occasional loss of flatus, 33 percent experienced involuntary losses of flatus, and 33 percent experienced involuntary loss of flatus and liquid stool.121 More favorable results have been reported by others, with 63 percent achieving complete continence and 79 percent of patients continent to both solid and liquid stool.109 However, the explanation rate is 20 to 37 percent.121–123 In a multi-center cohort study,110 a total of 384 device related or potentially device related adverse events were reported in 112 enrolled patients. Revisional surgery was required in 46 percent of patients.123 A lack of sensation for evacuation has been reported.121,124 Absolute contraindications for this procedure include active perineal sepsis, Crohns disease, radiation proctitis, severe scarring in the perineum, or anoreceptive intercourse. The artificial bowel sphincter seems most applicable to patients with substantial disruption of the anal sphincters.125 As the experience with artificial bowel sphincter has increased, explanation and infection rates seem to have decreased.121,123,124,126

10. The SECCA procedure may be useful for selected patients with moderate fecal incontinence. Level of Evidence: IV; Grade of Recommendation: C.

The SECCA procedure consists of the delivery of temperature controlled radio frequency energy to the anal sphincters. It is believed that the heat generated causes collagen contraction, healing, and remodeling, leading to shorter and tighter muscle fibers.127

In a pilot study of ten patients, the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Scale Score improved from 13.8 at baseline to 7.3 at two years, with corresponding improvement in quality of life scales.128 In a multi-center trial of 50 patients, there was a similar improvement in the Incontinence Scale score from 14.5 to 11.1 at six months. Complications included mucosal ulcers and delayed bleeding.129 Otherwise the procedure seems to be safe and may be performed as a day procedure. Long-term results are unknown.

11. A stoma (colostomy or ileostomy) is appropriate for patients with limiting fecal incontinence in which available treatments have failed, are inappropriate because of comorbidities, or when preferred by the patient. Level of Evidence: III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

A stoma is typically successful in controlling the problems of fecal incontinence but may be associated with significant psychosocial issues and stomarelated complications. It is particularly suited for patients with spinal cord injuries or patients who are bedridden.97,130,131 Because a stoma in this situation is usually permanent, appropriate siting of the stoma and counseling is very important.89In patients with severe fecal incontinence in which alternative therapy has failed or is inappropriate, a stoma will usually allow the patient to resume normal activities and improves quality of life.89,132 In a survey, 83 percent of patients with a permanent colostomy reported a significant improvement in lifestyle, and 84 percent of patients would choose to have the stoma again.132