Practice Parameters for the Evaluation and Management of Constipation

Charles A. Ternent, M.D., Amir L. Bastawrous, M.D., Nancy A. Morin, M.D., C. Neal Ellis, M.D., Neil H. Hyman, M.D., W. Donald Buie, M.D., and The Standards Practice Task Force of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring highquality patient care by advancing the science, prevention, and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. The Standards Committee is composed of Society members who are chosen because they have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and rectal surgery. This Committee was created to lead international efforts in defining quality care for conditions related to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive, and not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on which decisions can be made, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. These guidelines are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers, and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed by the topics covered in these guidelines.

It should be recognized that these guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all of the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

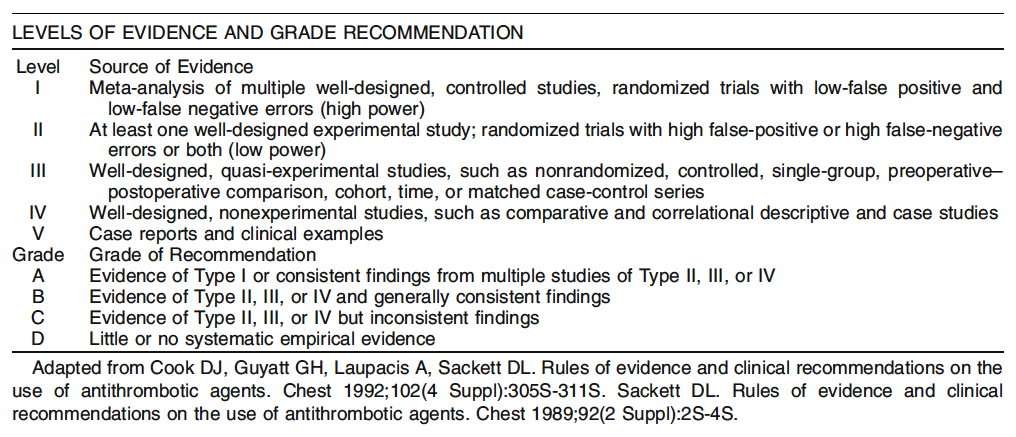

METHODOLOGY

An organized search of MEDLINE, PubMed, and the Cochrane Database of Collected Reviews was performed through October 2006. Keyword combinations included constipation, obstructed defecation, slow transit, surgery, rectocele, rectal intussuception, pelvic dyssynergia, anismus, paradoxical puborectalis, and related articles. Directed searches of the embedded references from the primary articles also were accomplished in selected circumstances.

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Constipation is a symptom based disorder of unsatisfactory defecation that may be associated with infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both.1 The diagnostic criteria for functional constipation according to the Rome III consensus include two or more of the following symptoms: straining, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction, and manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation more than 25 percent of the time, and less than three unassisted defecations per week. These symptoms need to be present for at least three days per month during the previous three months with symptom onset at least six months before diagnosis.2 Loose stools must be rarely present without the use of laxatives, and there must be insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).2 The symptoms of chronic constipation frequently overlap with constipation predominant IBS.1 The Rome III diagnostic criteria for IBS include abdominal pain or discomfort at least three days per month in the previous three months (symptom onset more than 3 months before diagnosis) with two or more features: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool and/or change in the form of stool.2 Sub-classification into constipation predominant IBS (IBSC) based on the Rome III criteria also requires the presence of Bristol Stool Form Scale Types 1 and 2.2 The numerous possible disorders leading to constipation argue for individualized evaluation and management according to the nature, extent, and chronicity of this common problem.1,3

EVALUATION OF CONSTIPATION

1. A problem specific history and physical examination should be performed in patients with constipation. Level of Evidence: Class IV; Grade of Recommendation: B.

A history and physical examination may identify the presence of alarm symptoms and signs, such as hemochezia, weight loss of more than 10 pounds, family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, anemia, change in bowel habits or blood in the stool, which suggest the need for more aggressive endoscopic and/or radiologic evaluation.1,4 An adequate history may help to identify factors associated with constipation, such as immobility, psychiatric illness, contributing medications, endocrine etiologies, such as diabetes and hypothyroidism, previous pelvic surgery, or symptoms consistent with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).2,5–10 The history may suggest the presence of obstructed defecation if there is straining with bowel movements, incomplete evacuation, sensation of obstructed defecation, and the use of manual maneuvers to aid defecation.11 Nevertheless, symptoms alone may not reliably distinguish slow transit constipation from anorectal dysfunction.1,5

A physical examination, including digital rectal examination, plus the selective use of anoscopy and proctosigmoidoscopy may identify the presence of fecal impaction, stricture, external or internal rectal prolapse, rectocele, paradoxical or nonrelaxing puborectalis activity, or a rectal mass.2,6,12

2. The routine use of blood tests, xray studies, or endoscopy in patients with constipation without alarm symptoms is not indicated. Level of Evidence: Class V; Grade of Recommendation: D.

Evidence to support the routine use of blood tests, radiography, or endoscopy in the routine evaluation of patients with constipation without alarm features is lacking.13 Nevertheless, endoscopic evaluation of the colon is justified for patients who meet criteria for screening colonoscopy or those with alarm features.2,14 Furthermore, blood tests may be helpful to rule out hypercalcemia and/or hypothyroidism.

3. Anorectal physiology and colon transit time investigations may help to identify the underlying etiology and improve the outcome in patients with refractory constipation. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

A review of 31 studies of colectomy for constipation found that preoperative physiologic tests, including at least anorectal manometry, defecography, and transit study, resulted in a median satisfaction rate of 89 percent compared with 80 percent for an incomplete physiologic evaluation.15 Studies in which slow colonic transit had been documented before colectomy for refractory constipation also reported an improved rate of good outcomes (90 vs. 67 percent).15,16

The balloon expulsion test is a simple screening procedure to exclude pelvic floor dyssynergia (PFD), because symptoms alone may not be enough to distinguish between slow transit constipation and outlet obstruction.17,18 A prospective study of balloon expulsion in patients with constipation found a specificity and negative predictive value for excluding PFD of 89 and 97 percent, respectively. A nonpathologic balloon expulsion test may avoid the use of other pelvic floor investigations, such as anorectal manometry, surface EMG studies, and defecography.19

Anorectal manometry and surface anal electromyography may help to confirm pelvic floor dyssynergia or anismus.14 The presence of Hirschprungs disease also can be suggested by anorectal manometry when the rectoanal inhibitory reflex is absent.12 Defecography is probably the most useful diagnostic technique for identifying internal rectal intussuception. In the setting of obstructed defecation, defecography may help to detect structural causes, such as intussuception, rectocele with retained stool, pelvic dyssynergia, and extent of rectal emptying. Defecography has been shown to have good interobserver agreement for enterocele and rectocele and fair to moderate inter-observer agreement for intussuception and anismus.20

The measurement of colon transit time using radio paque markers in patients with suspected slow transit constipation is inexpensive, simple, and safe. There are different methodologies that produce similar results,21–25 including the use of radioisotope markers.26–28 The interpretation of colon transit studies may be facilitated by knowledge of the status of the pelvic floor in the patient with constipation.29 Some studies have not found a relationship between smallbowel function and functional results after total abdominal colectomy for colonic inertia.30 However, a longterm, prospective study did suggest that patients with generalized gastrointestinal disorder (GID) have a diminished longterm success rate after colectomy (13 percent GID vs. 90 percent no GID).31 Similarly, a high postoperative morbidity from recurrent smallbowel obstructions (70 percent) exists in patients with GID.32

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF CONSTIPATION

1. The initial management of symptomatic constipation is typically dietary modification, including a high fiber diet and fluid supplementation. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Conservative measures should be attempted before surgical intervention for constipation.33 Empiric treatment for constipation with a high fiber diet seems to be an inexpensive and effective therapeutic intervention for addressing constipation related bowel dysfunction.8,34 The daily intake of 25 g of fiber per day has been shown to increase the stool frequency in patients with chronic constipation. Furthermore, increasing fluid intake to 1.5 to 2 liters per day has been shown in a randomized, clinical trial of chronic constipation to increase stool frequency and decrease the need for laxative in individuals already consuming a high fiber diet.34 Increased physical activity also seems to be helpful.35

2. The use of polyethylene glycol, tegaserod, and lubiprostone for the management of chronic constipation is appropriate when dietary management is inadequate. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: A.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) can be used to promote bowel function in patients with chronic constipation. A randomized, clinical trial found that daily therapy with 17 g of PEG laxative for 14 days resulted in significant improvement of bowel movement frequency in patients with constipation compared with placebo at two weeks.36 Prokinetic agents, such as the 5HT4 receptor partial agonist tegaserod maleate, can be used for treatment of constipationpredominant IBS. Seven short term, placebo controlled studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the Cochrane review in patients with constipation predominant IBS. Tegaserod improved the number of bowel movements and days without bowel movements compared with placebo.37 Another systematic review found good evidence to support the use of PEG and tegaserod for the treatment of constipation.38 Furthermore, clinical outcome analysis of a single blind, randomized, multi-center trial of the treatment of idiopathic constipation during three months with PEG or lactulose showed that significantly more patients were successfully treated with PEG than lactulose (53 vs. 24 percent) with overall decreased total management costs.38

Lubiprostone (Amitiza) is an oral bicyclic fatty acid that selectively activates Type 2 chloride channels in the apical membrane of the gastrointestinal epithelium, resulting in increased fluid secretion. Two randomized, double blind, multi center, Phase III studies in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation have shown that the frequency of spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) was significantly greater in patients receiving lubiprostone 24 mg twice per day than in those receiving placebo at each weekly time point throughout both four week studies (P < 0.05). One study found that the mean frequency of SBMs in the lubiprostone group was five per week compared with four per week in the placebo group after seven days (P < 0.0001). Significantly greater improvements occurred with lubiprostone than placebo in the degree of straining, stool consistency, and constipation severity in both studies at all time intervals up to four weeks (P < 0.05).40 3. The use of psyllium supplements and lactulose for the treatment of chronic constipation is appropriate. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B. A systematic review of the literature found that psyllium and lactulose improved symptoms of constipation.38 A prospective, non-randomized trial studied 224 patients with simple constipation who were treated with ispaghula husk and 170 patients who were treated with other laxatives, mostly lactulose, for up to four weeks. The husktreated group produced a higher percentage of normal, wellformed stools and fewer hard stools than other laxatives. The husk was found to be an effective treatment for simple constipation with better stool consistency and lower adverse events compared with lactulose or other laxatives.41 4. The use of common agents, such as milk of magnesia, senna, bisacodyl, and stool softeners, for chronic constipation is reasonable. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: C. Various laxatives may be used for chronic constipation but there are inconsistent results in the literature. A metaanalysis38 found 11 large, well controlled, published studies regarding the efficacy of laxatives in constipation. There were 375 patients taking laxatives and 174 patients taking placebo. The treatment group was noted to have a mean increase of 0.9 stools per week and a mean increase in stool weight of 42 g, but these findings were not different than the placebo effect at a four week duration.38,42 Furthermore, long term laxative usage can result in the development of cathartic colon.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Slow Transit Constipation

1. Patients with refractory slowtransit constipation may benefit from total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (TACIRA). Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Clinical improvement with total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (TACIRA) is reported in 50 to 100 percent of patients with slowtransit constipation (STC).43 The results of segmental colon resection for colonic inertia have been disappointing with some small series reporting up to a 100 percent failure rate.15 Similarly, the antegrade colonic enema (ACE) procedure has been described for treatment of intractable constipation. Nevertheless, studies have shown a 33 percent conversion rate to TACIRA with associated stoma complications, wound infection, pain, and psychologic problems in adults.44,45 TACIRA has been reported to have an 8 to 33 percent morbidity from recurrent bowel obstruction and can be associated with diarrhea, incontinence, and recurrence of constipation.43 Patients should be counseled that the abdominal pain and bloating may persist postoperatively even after normalization of bowel frequency.7 A retrospective study of 55 patients after TACIRA for colonic inertia with normal anal manometry identified prolonged postoperative ileus in 24 percent of cases. Good to excellent results were reported in 89 percent of patients and poor results in 11 percent. Postoperative stool frequency was 5, 4, and 3 per day at 1, 2, and 12 months, respectively.46 TACIRA is recommended for carefully selected patients with severe documented colonic inertia and no evidence of severe or correctable pelvic floor dysfunction after nonoperative treatments have failed.15,16,31,46–51 Although constipation is generally relieved after TACIRA, studies have shown that, postoperatively, 41 percent of patients are affected with abdominal pain, 65 percent with bloating, 29 percent require assistance with bowel movements, 47 percent have some incontinence to gas or liquid stool, 52 and 46 percent may be affected with diarrhea.53 Postoperative quality of life assessment after TACIRA showed significantly decreased scores compared with those of the general population.52 Nevertheless, 93 percent of carefully selected patients with TAC would undergo colectomy again for STC given the chance.53 An ileostomy is an alternative consideration in many of these patients. 2. Refractory slowtransit constipation associated with concomitant pelvic outlet obstruction may benefit from correction of the pelvic floor dysfunction and total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: B. Studies of colectomy for refractory constipation have demonstrated successful outcomes for TACIRA in 89 to 100 percent after preoperative workup, including colon transit study, defecography, and anorectal physiology investigation.15 A thorough preoperative workup may help to exclude patients with constipationpredominant IBS or normaltransit constipation who will be unlikely to benefit from surgical intervention. Furthermore, patients with combined STC and outlet obstruction pathology may be offered individualized management.16,31,47–51 STC and associated pelvic floor dyssynergia can be treated with biofeedback and TACIRA, although this group has been shown to have a higher rate of recurrent defecatory problems and lower satisfaction rates after colectomy.15 STC with rectal intussuception and/or nonemptying rectocele/enterocele can be treated with TACIRA after repair of the anatomic cause of the outlet obstruction.47,50

MANAGEMENT OF PELVIC FLOOR DYSSYNERGIA

1. Biofeedback therapy is appropriately recommended for treatment of symptomatic pelvic floor dyssynergia. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

The success rates of biofeedback for the treatment of PFD are reported to be 35 to 90 percent.54–56 A recent, randomized, clinical trial of individuals with chronic severe PFD who had failed management with 20 g per day of fiber plus enemas or suppositories up to twice per week were randomized into five weekly biofeedback sessions (n = 54) or PEG 14.6 to 29.2 g per day plus five weekly sessions in constipation prevention. Stool frequency increased in both groups. However, at six months major improvement was reported in the biofeedback group in 80 percent compared with 22 percent of patients treated with laxatives. These results of biofeedback were sustained at 12 and 24 months along with reductions in straining, sensations of incomplete evacuations, blockage, use of enemas and suppositories, and abdominal pain. Biofeedback patients reporting the major improvement in symptomatology were able to relax the pelvic floor and evacuate a 50ml balloon at 6month and 12month followup. Therefore, biofeedback seems to be the treatment of choice for PFD.57

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF OBSTRUCTED DEFECATION

Surgical Procedures Indications for rectocele repair vary but generally include relief of the outlet obstruction symptoms with manual support of the vaginal wall or rectum and lack of rectocele emptying on defecography. Although controversial, some propose that rectoceles should be > 4 cm in size to warrant repair.58

1. Surgical repair of a rectocele may appropriately be performed via a transvaginal approach. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: C.

The traditional technique for transvaginal rectocele repair is a nonanatomic, longitudinal plication of the rectovaginal fascia with the repair continuing onto the perineal body in which any injuries to the puborectalis and perineal muscles also are addressed.59 This technique is reported to be successful in preventing vaginal bulging in 80 percent and corrects the need for digital assistance of defecation in 67 percent of patients.58,59 Less favorable clinical results have been reported with a failure to relieve evacuatory difficulty or lower rectal symptoms in 33 percent of patients. Postoperative dyspareunia will occur in 25 percent of patients and at least 10 percent may recur and require reoperation; 36 percent will report a problem with fecal incontinence.60–63 A prospective study of rectocele repair using xenograft has been reported.64 Although significant decreases in rectal emptying difficulties were noted, cure of the rectal emptying difficulties was reported by less than half of the patients at the threeyear followup.64

Recently, the concept of an anatomic defect specific transvaginal rectocele repair has been described. In this technique, the defect in the rectovaginal fascial defect is closed transversely. During the shortterm, results with this technique seem encouraging with the symptom of constipation improved in more than 80 percent of patients and a low incidence of recurrent clinical rectocele or postoperative need for digital assistance of defecation.63,65–68 A pilot study of 30 randomized patients comparing transvaginal to transrectal rectocele repair found that symptoms of outlet obstruction were significantly alleviated by both approaches (93 percent in the vaginal group and 73 percent in the transrectal group), but the transvaginal technique had less recurrent rectoceles than the transrectal approach (7 vs. 40 percent).69 None of the patients developed postoperative de novo dyspareunia in this study; however, the sample size was small.69

2. Surgical repair of a rectocele may appropriately be performed via a transrectal approach. Level of Evidence: Class II; Grade of Recommendation: B.

Although transrectal repairs of rectoceles were described in the mid 1960s, the suboptimal results in terms of bowel and sexual function of the transvaginal repairs led to the rediscovery and popularity of these techniques in the 1980s.70–72 Another benefit of transanal repair is the ability to address the coexistent anorectal pathology that will be present in up to 80 percent of patients.73

The transrectal, anatomic, defectspecific rectocele repair involves the transverse closure of the rectocele by an interrupted plication of the muscularis anteriorly as in a Delorme procedure for rectal prolapse. This method results in a relative foreshortening of the anal canal with diminished internal sphincter function and resting anal pressures leading some to conclude that this procedure is contraindicated in patients with combined fecal incontinence and rectocele.74–76

An alternative is a nonanatomic technique in which the defect is repaired longitudinally by approximating the musculofascial edges of the defect. This repair tends to be under tension but does lengthen the anal canal, which may address the potential for worsening of fecal incontinence with the anatomic repair.77,78

The results with either of these techniques are comparable with evacuatory difficulty improved in 47 to 84 percent, correction of the need for digital assistance of defecation in 54 to 100 percent, and decreased constipation in 48 to 71 percent. Most of the variations in results seem to be related to differences in patient selection and criteria for evaluating the outcomes.

3. The role of transperineal techniques or the use of prosthetic mesh for rectocele repair is uncertain. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: D. Transperineal surgery for rectoceles has been recommended in combination with a conventional sphincteroplasty and/or levatorplasty for the management of patients with a symptomatic rectocele and incontinence secondary to a sphincter defect. Short term results of this combined procedure show an improvement in evacuation and continence in 75 percent of patients.79 The transperineal insertion of a prosthetic mesh has been described with a significant reduction in the need for digital assistance of defecation and in the size and amount of barium retained in rectoceles.80 Controlled clinical trials of this technique need to be performed before the role of this procedure in the management of rectoceles can be determined.

4. The role of transrectal stapled repair of rectoceles and rectal intussuception is uncertain. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: D.

The repair of rectoceles and internal intussuception using endoanal staplers has been reported and continues to be investigated. Initial results with the stapled rectocele repair are encouraging in terms of evacuatory improvement, but currently there are no studies comparing it to other methods, nor are longterm outcomes known.81–92 There are reports of postoperative bleeding, pain, incontinence, constipation, and rectovaginal fistula using this technique.93,94

5. Surgical repair for rectal intussusception associated with severe, intractable symptoms of obstructed defecation may be considered as a last resort. Level of Evidence: Class III; Grade of Recommendation: C.

A study evaluating the Ivalon rectopexy for treatment of rectal intussuception and outlet obstruction failed to cure defecatory difficulties. Rectopexy was recommended for intussuception associated with ulcer and bleeding but not for those with obstructed defecation symptoms.95 The Delorme repair has been reported in 21 patients with intussuception and outlet obstruction with improvement of symptoms in 71 percent and no recurrent intussuception.96 The Wells rectopexy has been reported to result in defecographic resolution of the intussuception in 92 percent, but complete symptomatic relief was rare.97 A study of rectopexy for treatment of internal intussuception resulted in 70 percent resolution of symptoms and healing of all rectal ulcers.98 The Ripstein procedure was shown to achieve complete resolution of symptoms in 20 percent, partial resolution of outlet obstruction symptoms in 32 percent, and no improvement or worsening symptoms in 48 percent.99

Based on these case series, surgical management of internal intussusception may be considered for those with solitary rectal ulcer and possibly for associated intractable symptoms of outlet obstruction but only after conservative management has failed.